There’s No Environmental Justice Without Racial Justice

As we celebrate Black History & Black Futures Month this February, the connections between environmental justice and racial justice are clearer than ever.

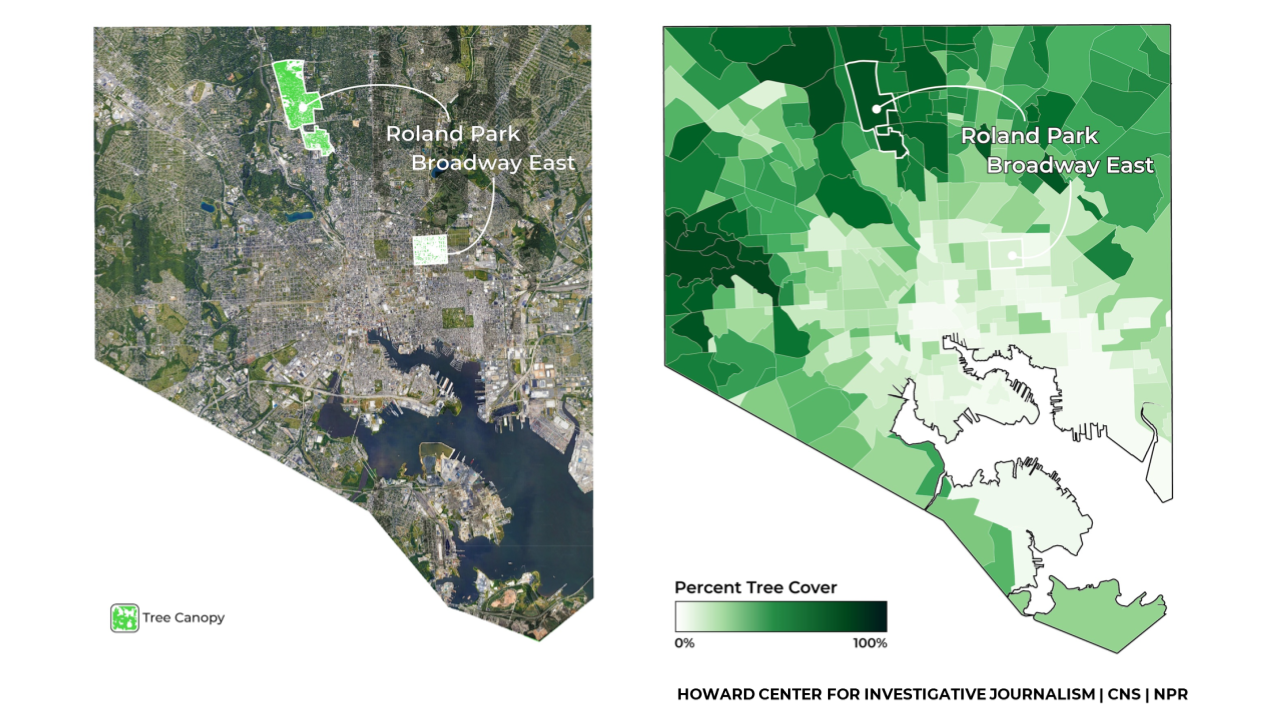

As a majority white organization working in a majority Black city, we at Blue Water Baltimore strive to uphold a commitment to equity and also recognize that we have a lot more work to do to center racial justice in our work. We know that the issues we work on affect people differently depending on their race. For example, predominantly Black Broadway East has six times less tree canopy than predominantly white Roland Park, which can lead to significant temperature differences between these two neighborhoods. And data has shown that predominantly Black neighborhoods are more likely to experience dangerous sewage backups than predominantly white neighborhoods as a result of inequitable investments in city infrastructure. This means that Black Baltimoreans are bearing the brunt of the urban heat island effect and the health and financial burdens posed by residential sewage backups in clear examples of environmental racism.

And, as a majority white organization, we benefit from the work and calls-to-action of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) to move us forward. This month (and many going forward), we are reflecting on the long history of BIPOC leadership in the environmental justice movement and the direct links between racial inequities and environmental injustice. We hope our supporters, particularly our white supporters, will join us in this learning and take action in support of environmental and racial justice.

The Roots of Environmental Justice

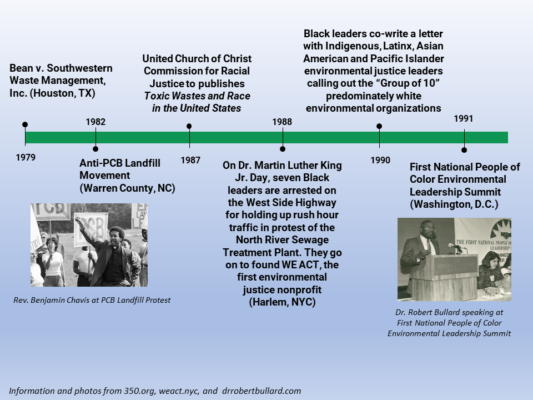

The environmental justice movement was founded by and is primarily carried by Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, who have been consistently impacted by the negative effects of environmental pollution and policy in the U.S. and many other countries. The timeline below outlines just a few of the actions and organizers that catalyzed the movement to reclaim community autonomy, health, and safety.

Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management

In 1979, Margaret Bean and other Houston residents filed a lawsuit against a plan to locate a municipal landfill next to their homes in an 82% Black neighborhood. The lawsuit was the first in the U.S. to charge environmental discrimination in waste facility siting under civil rights laws.

Warren County Anti-PCB Landfill Movement

In 1982, North Carolina created a landfill in predominantly Black Warren County to dump soil contaminated with PCB. Warren County residents led a six-week stretch of direct action against the landfill during which they put their bodies on the line in front of 10,000 truckloads of PCB-contaminated soil, leading to 550 arrests. This highly visible action is often credited with launching the environmental justice movement and marked the first instance of arrests due to protests against a waste facility in the U.S.

Toxic Waste and Race

In 1987, the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice released its groundbreaking report “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States.” The report concluded that race is the most significant factor in predicting where commercial hazardous waste facilities are located in the U.S., affirming what many frontline communities had been pointing out for years.

Founding of WE ACT

On Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 1988, the “Sewage Seven” were arrested on the West Side Highway for holding up rush hour traffic to call attention to how the poor operation of the North River Sewage Treatment Plant was responsible for an increase in incidents of respiratory illnesses being experienced by local residents. These activists incorporated the same year in New York State as West Harlem Environmental Action, Inc., now known as WE ACT, which is still active in New York as well as in D.C.

Letter to the “Group of 10”

Hundreds of BIPOC cultural, arts, community, and religious leaders wrote a letter in 1990 to the directors of the “Group of 10” big conservation groups outlining the organizations’ history of racism, lack of diversity, and failure to center environmental justice. The letter exposed the rift between “environmentalism” and environmental justice by highlighting the racism and injustice within the environmental movement.

EJ Summit

In 1991, over 700 BIPOC leaders from all 50 states gathered for the first National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. The four-day summit demonstrated the power of multi-racial grassroots organizing for environmental and economic justice. One of the most lasting outcomes of this summit was the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice which were arrived at by consensus-building and continue to be used by organizers today.

Environmental Racism – Broadening Our Analysis

Since the launch of the environmental justice movement, there has been a growing recognition of the disproportionate siting of polluting facilities like incinerators and coal plants near communities of color. Many people are familiar with the Dakota Access Pipeline project on Standing Rock Sioux land and, more locally, the BRESCO trash incinerator in South Baltimore. But environmental justice advocates and organizers make it clear that environmental racism goes beyond where polluting facilities are sited and includes numerous aspects of how the environment affects BIPOC in their daily lives.

Climate justice writer Mary Annaïse Heglar expands upon what we should include in our understanding of environmental racism:

“It’s time to talk about how extreme heat begets extreme violence—and how that can interact with an already extremely violent police force. It’s time to talk about how extreme heat exacerbates police violence and increases deaths from tasers. It’s time to talk about what happens in prisons, which often lack air conditioning and heat, as temperatures skyrocket. It’s time to talk about climate gentrification. It’s time to talk about the use of tear gas — which hurts respiratory systems during a pandemic that is already disproportionately affecting Black people — as environmental racism.”

From a white woman calling the cops on a Black birdwatcher in Central Park to Black mothers experiencing higher instances of pregnancy risks due to climate change, environmental racism is entrenched in and affects so many facets of our society. As the calls for racial justice grow louder around the country, it’s critical that the environmental movement step up to fight for environmental justice on all fronts.

Resources

- We encourage you to look up and support BIPOC-led orgs continuing this fight for environmental justice right now. Start with the Climate Justice Alliance, The Chisholm Legacy Project, and our own local partners the Baltimore Tree Trust and Black Yield Institute.

- You can find out whose land you’re on at Whose Land and how to pay reparations from Resource Generation.

- Deepen your knowledge about environmental justice. Here are some places to start:

- Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors by Carolyn Finney

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Cooked: Survival by Zip Code PBS documentary

- DISRUPTION: Baltimore’s Highway to Nowhere short documentary on YouTube

- Hot Take podcast & newsletter by Mary Annaïse Heglar and Amy Westervelt

- Red, Black & Green New Deal by The Movement for Black Lives

- The Coolest Show on Climate Change podcast from the Hip Hop Caucus

- There’s Something in the Water documentary on Netflix

- The Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution by Robert D. Bullard

- Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility by Dorceta Taylor

And finally, stay in conversation! We all learn more together and from one another, and Blue Water Baltimore is here to learn with you. We welcome feedback and questions in the comments or to [email protected].