TRANSFORMING A 3000 ACRE STEELMAKING COMPLEX FROM HAZARDOUS WASTE SITE TO A RESTORATION SUCCESS

Reprinted with the permission of the American College of Environmental Lawyers (ACOEL)

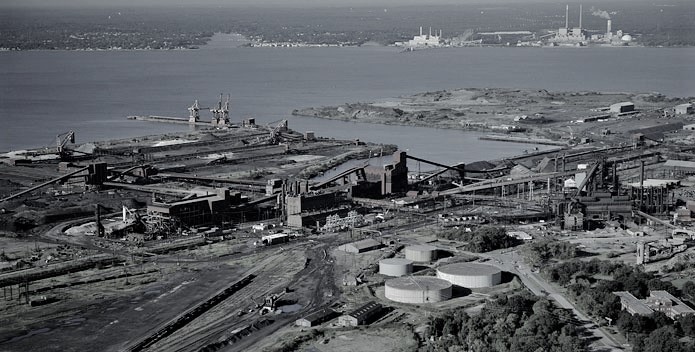

In 1959 Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point facility, located on the Patapsco River near the mouth of Baltimore Harbor, was the biggest steelmaking facility in the world. With close to 40,000 employees, Sparrows Point over many decades produced the steel that built bridges, buildings and railroads across America, plus ships and weaponry for World Wars I and II, and the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Sprawled across 3000 acres were blast furnaces, coke ovens, open hearth furnaces, rod and wire mills, a shipyard, electroplating operations, facilities for producing slabs and sheets of steel, plus raw material storage buildings.

In 1975, while at EPA, I visited this plant, and the sheer magnitude of the operations was unlike anything I had ever seen. Molten steel was being poured into enormous vats or molds. The heat, noise and dust were overpowering. Over 100 miles of railroad track enabled raw material, product and equipment to be transported across the complex. But by then the American steel industry, facing strong foreign competition, was in financial difficulty, leading to cutbacks in maintenance and expenditures for environmental compliance. Decades of steelmaking had produced enormous quantities of hazardous wastes, including metals and organics, which were disposed of in unlined ditches and ponds, or simply dumped on the ground. This resulted in contamination of soils, surface water and groundwater, and runoff into the Patapsco River. One such unlined impoundment was over a mile long, 80 feet wide, and according to EPA received at least 36 types of RCRA hazardous waste.

Because Sparrows Point was the biggest employer in the state, EPA and the Maryland Department of the Environment did little to enforce compliance with environmental laws despite major violations throughout the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s. In 2001 Bethlehem Steel declared bankruptcy. A series of successors struggled unsuccessfully, with vastly scaled back operations, to produce steel. Virtually nothing was spent to contain the vast amounts of hazardous waste which continued to migrate offsite.

By 2010, after 30 years with Crowell & Moring, I was doing pro bono work with the Chesapeake Legal Alliance. On behalf of the Baltimore Harbor Waterkeeper, and in partnership with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) which was separately and ably represented, we filed a citizen suit against the then current operator, Severstal, under RCRA and the Clean Water Act seeking injunctive relief, cleanup of contamination, and compliance with closure and post-closure care requirements. The Waterkeeper organization had members who lived in an economically disadvantaged, largely Black community near the plant known as Dundalk. Residents liked to swim, fish and crab in Bear Creek, a tributary to the Patapsco, which received significant pollution from the plant via surface runoff and groundwater migration. This public health threat gave urgency to the need to clean up the site.

Financed by insurance, Severstal hired lawyers to vigorously defend the litigation. We battled through discovery and hired experts, but in May, 2012, Severstal’s successor, R.G. Steel, filed for bankruptcy, and that halted the lawsuit. We persuaded the bankruptcy judge to require R. G. Steel to contribute $500,000 to a fund for off-site remediation, but that was a tiny fraction of what was needed.

As the assets of this once booming enterprise were being dismantled and sold off, a group of investors decided to buy the property, clean it up, and develop it for commercial occupancy using long-term leases. Helpfully, the property has a deep water port, railroad access, and proximity to an interstate highway. It was a bold move, and one that is turning out to be a life-saver for the property, the greater Baltimore community and the environment. The investors formed a company now known as Tradepoint Atlantic (TPA), which acquired the property as a “bona fide purchaser” of a site whose contamination it did not cause or contribute, enabling it to secure Superfund protection though a Settlement Agreement with EPA executed in September, 2014, and comparable protection under Maryland’s voluntary cleanup law.

TPA simultaneously executed an Administrative Consent Order with the Maryland Department of the Environment requiring it to clean up the entire site in compliance with RCRA and corresponding state law. It posted $45 million as financial assurance, which must be reviewed regularly and refreshed as needed. Because in Maryland EPA has the lead for RCRA Corrective Action, EPA’s Settlement Agreement includes that role. TPA also settled any claim for Superfund liability for past off-site releases with a payment of $3 million. Those historic releases were addressed by EPA initially as a removal action, but when contaminated sediment turned out to extend across some 60 acres, EPA is now moving to list it on the NPL.

To clean up the site, TPA divided it into roughly 50 parcels, usually based on specific process operations or waste disposal locations. Under the ACO and Settlement Agreement, TPA conducts a soil and groundwater investigation, then proposes remedial actions, which are reviewed and critiqued by EPA and MDE, and are proposed for public comment before being approved. Public meetings are held by the agencies semiannually. The Waterkeeper early on merged with other local organizations to form Blue Water Baltimore. On its behalf, along with CBF, we routinely monitor compliance with the ACO and Settlement Agreement, filing comments and challenging inadequate protection of public health or the environment whenever we see it. We have periodic disagreements with the agencies, but the process is generally working.

TPA has a financial incentive to clean up each parcel promptly, since only then can it enter leases and start recouping its costs. At this point about 20 parcels have been cleaned up and leased out to tenants such as Under Armor, Federal Express, Amazon and Home Depot. Ten thousand jobs have been created, plus some 2000 short-term construction jobs, providing a boon to Baltimore’s economy at a facility which would otherwise be languishing, producing nothing of value, and leaching toxic waste into the environment. Isn’t this what we hope for when we restore abandoned industrial sites?

Ridge Hall can be reached at <[email protected]>

Want to read more articles like this? Sign up for our ‘Advocacy’ mailing list today

[maxbutton id=”5″ url=”https://bluewaterbaltimore.us16.list-manage.com/subscribe?u=9bdffb01b74379007ad56c395&id=9a25dfb1ce” ]