Baltimore’s Sewage Issues Are Rooted in Racial Injustice

By Matthew Price

As we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. and the progress toward racial justice in the U.S., we must honor King’s legacy by acknowledging the long road left ahead and recommit to fighting for racial justice everyday. In Baltimore, racial inequity continues to affect everything from life expectancy rates to commute times. And the city’s water and wastewater infrastructure is no different. Many of the problems with Baltimore’s sewer infrastructure and high rates of basement backups are rooted in redlining; a systematic racial policy that dates back to the 1930s. Redlining blocked majority Black neighborhoods from receiving proper investment in schools, transportation, and infrastructure; and its legacy can be seen in Baltimore’s sewage problems today.

Background

Unlike other American cities, Baltimore City did not even have a sewer system until 1905. Once finally built, this early 20th century infrastructure was left virtually untouched until the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)sued Baltimore for violating environmental regulations about 20 years ago and the city entered into a consent decree with the EPA and the Maryland Department of the Environment. Prior to the consent decree, when the system and pipes overflowed with too much wastewater, the city relied on overflow valves to direct excess sewage into Baltimore’s waterways. Under the consent decree, all the relief valves were eventually closed except two. While this reduced the damage the city was inflicting on its waterways, it caused another issue: basement backups. When pipes cannot handle the overflow, it has nowhere to go but back into residents’ homes.

Racial Inequality

Majority African American communities in Baltimore bear the brunt of sewage backups, experiencing more backups and worse sewage infrastructure than predominantly white communities. Using 311 data, the system by which the city’s Department of Public Works (DPW) records all reported backups in the city, the top five neighborhoods experiencing the most backups from 2021-2022 were all predominantly African American communities. Loch Raven, with a population which is 87% African American, was the highest with 525 reported backups . A Johns Hopkins University study concluded that as African American population rates increase in a Baltimore neighborhood, there was an increase in the frequency of basement backups. The higher rates of sewage backups in Black communities can be linked to the legacy of redlining and a long history of environmental racism and inequitable investments in infrastructure between Black and white neighborhoods.

And since redlining and other racist policies have left an ongoing chasm between Black and white household wealth, costly sewage backups tend to hit Black households harder.. Consider the difference between how a sewage backup impacts a resident of Canton, which is 79.9% White with a median household income of $134,208 in 2020, and a resident of Pimlico, Arlington, and Hilltop in Northwest Baltimore, which is 90.7% African American and has a median house income of $34,041. While Canton recorded 175 backups between 2021 and 2022 and Pimlico, Arlington, and Hilltop recorded 218 backups in the same period, the impact on residents of these neighborhoods is dramatically different, due to the significant financial resources required to respond to a sewage backup.

DPW runs two programs to support residents who face basement backups: the Expedited Reimbursement Program (ERP) and Sewage Onsite Support (SOS). When a resident has a backup in their home, they can file a claim for financial reimbursement for the cost of cleanup up to $5,000 under the ERP. Under the SOS, residents can call 311 and DPW will send a contractor to clean up the backups for free if the backup is deemed eligible. However, both programs lack the coverage and flexibility to offer adequate aid to most residents. The strict criteria and bureaucratic complexity involved in qualifying for and receiving reimbursement and cleanup support mean that few residents qualify for assistance. Since 2018, there have been 194 claims submitted to the ERP, but only 19 have been approved, less than 10% of all applications. This is partly because the ERP covers only wet weather claims – despite the fact that most basement backups occur in dry weather.

ERP application data shows that the average basement backup cleanup costs $5,971.80. Given low median household incomes, this amount is prohibitive for many Baltimoreans. Basement backups result in severe financial and mental stress, and compromise residents’ health. If they cannot afford professional cleanups, many end up doing it themselves, leaving them exposed to diseases such as cholera, hepatitis A, and E. coli.

Minimal Progress

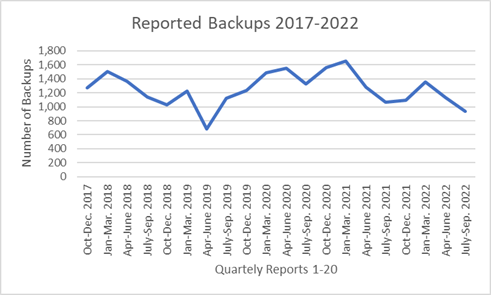

Baltimore City has made little progress in decreasing the frequency of backups, despite two decades of investment in the sewage system, as shown in Figure 1.

The road to better sewer infrastructure in Baltimore is long, but at minimum, the Department of Public Works (DPW) should direct effective sewage infrastructure upgrades to the underserved neighborhoods most affected by backups. More immediately, DPW should expand its reimbursement program and direct cleanup programs to include dry weather events so that more residents can access this critical support if they experience dangerous and costly sewage backups in their homes.

You can learn more about BWB’s recommendations to improve the ERP and SOS programs in this joint report with Clean Water Action. And if you’ve experienced a backup, report it through this confidential form and complete this survey to let us know if you reported the backup to the City and if you received assistance.

Matthew Price is a recent graduate of Towson University and volunteered as an Advocacy Research Intern with Blue Water Baltimore during the 2022 fall semester.