Baltimore’s Hidden City: a conversation with Sewer author, Jessica Leigh Hester

Miles of pipes snake below our feet, teeming with activity and unwitnessed by many. While most people turn a blind eye to sewer systems, Jessica Leigh Hester traverses this concrete jungle with unwavering curiosity. The Sewer author sat down with us ahead of World Water Day to shed light on the fragility, beauty, and vitality of these systems that we often overlook.

Jessica’s passion for wastewater infrastructure was born out of a March Madness-style bracket challenge she ran while writing for Atlas Obscura. “Mundane Madness,” as they called it, invited readers to submit and vote on the most transformative and under-appreciated inventions of the common era. Paper and sewers went head-to-head in the final matchup and, to Jessica’s surprise, support poured in for wastewater systems. “Librarians were reaching out [saying]… ‘haven’t you ever heard of cholera?’” This prompted Jessica’s initial exploration of this vital infrastructure—seeing sewers as a keystone at the intersection of ecology, urban planning, social justice, and pollution.

Among the many topics we discussed, Jessica’s points came back to a central thesis: sewers are fragile, often in a way we completely take for granted. Even in all their concrete grandeur, our infrastructure hinges on the support of thousands of maintenance workers, city planners, everyday residents. Looking back to the start of her research, Jessica mused “I hadn’t thought [that sewers need] ongoing maintenance from flesh and blood people.” This maintenance is best summed in a study of solidified waste in our sewer systems, commonly called fatbergs. These silent villains are the accumulation of fats, oils, and greases (FOGs) around a sticky matrix, often a wet wipe or piece of trash, that snags on a piece of corroded or clogged sewer pipe. From there, this accumulation sprawls—collecting more waste, FOGs, and trash—and can reach the size of a bus or even an airplane. Removing these giants necessitates an immense amount of labor, often requiring sanitation workers to break apart the masses with pickaxes and hand-tools. In 2017, a giant fatberg was removed near Baltimore’s Penn Station that caused more than 1 million gallons of sewage to overflow into the Jones Falls. (Warning, those photos are not for the faint of heart).

At Blue Water Baltimore, we often discuss the impacts of aging sewage infrastructure on the health of our waterways. After the Great Baltimore Fire in the early 1900s, the city installed a state-of-the-art “MS4” stormwater and wastewater system, marking the dawn of a new era for Baltimore. But today, decades of deferred maintenance to this century-old system have led to chronic sewage overflows into our waterways and sewage backups into residents’ homes, all while water bills continue to rise. Blue Water Baltimore consistently advocates for updates to this vital infrastructure, but Jessica also offered suggestions for individuals to take action on behalf of our treasured sewer system:

- Be much more discriminating about what you flush. Wet wipes, paper towels, floss, menstrual products, and other waste are not flushable… yes, even “flushable” wipes should not go down the pipes. “Pee, poop, puke, and paper” is Jessica’s prescription for the porcelain throne.

- Invest in a bidet. While bathroom overhauls aren’t feasible for many of us, clip-on bidets offer a cost- and space-effective solution to reducing flushable waste.

- Save the grease. No amount of fats, oils, and greases down the drain is safe—even when rinsed down with hot water and soap. Instead, sop up small amounts of grease with a paper towel, and dump large amounts into disposable containers to freeze, before throwing it all away in a trashcan.

- Make space for the sewers. Read, watch, and bear witness to the vital role this infrastructure plays in our lives, and learn how failing to invest in sewers impacts us all.

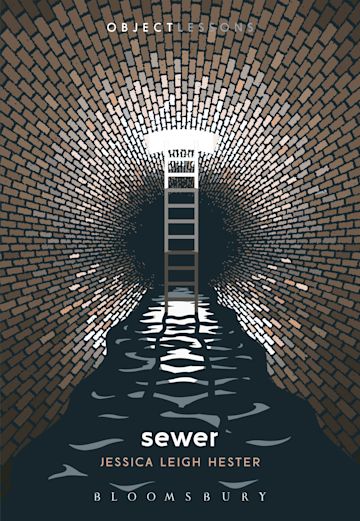

Sewer by Jessica Leigh Hester is available wherever you buy books, including at GreedyReads in Remington—just blocks away from the Blue Water Baltimore office.